Background

Aerial Surveys

Traditional aerial wildlife surveys typically use human observers in a low-flying airplane, counting wildlife by eye. These surveys track changes in wildlife populations (e.g. due to poaching) or responses to environmental changes (e.g. changes in the population of migratory wildebeest in the Serengeti from changing rainfall). Traditional aerial surveys are used in at least 25 countries in Africa, as well as Australia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and the USA. Surveys often only occur on 3-5 year intervals due to high logistical costs and the difficulty in fielding logistics, flight crew, fieldwork, and analysis teams in remote locations. Wildlife surveys provide valuable data about other targets such as human land use (livestock enclosures, thatched huts, etc.) and habitation that are often overlooked once a survey is complete. Combining land use and wildlife distribution maps allows managers to produce risk maps on potential human-wildlife-conflict that will benefit wildlife conservation in the long run. New survey methods using automated cameras show great promise, but the quantity of images to analyse leads to prohibitive cost and time increases.

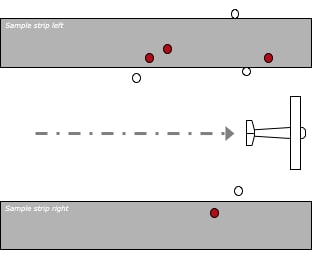

Aerial censuses of wildlife have been conducted since the 1950s in Africa, and since the late 70s, the dominant method used has been “Systematic Reconnaissance Flights” (SRF), and it is broadly applied in wildlife conservation globally8,9. The SRF sample count method is suitable for covering large areas to produce accurate maps and estimates. In these counts, one or more Cessna light aircraft, with crews of 4 people, fly straight sample lines across survey zones, taking days or weeks to cover partial areas of such enormous ecosystems. Two rear-seat observers (RSOs) on each aircraft count wildlife and other targets as the aircraft flies over points of interest.

Even though the SRF sample count method is widely adopted in wildlife conservation, concerns still exist, such as whether well-trained RSOs suffer from fatigue, which limits daily mission times, and RSOs can be highly variable in their performance. Fielding aircraft and crew is expensive and flying low-and-slow is dangerous work.